The childhood of photography

The camera as an invention is old. Already during the Renaissance, there were projection systems that would help artists depict objects in their drawings and paintings. The road to today’s photography began in the 18th century, when experiments were made to make the projected image stick to a material. The first successful attempts were short-lived; the image faded away shortly after becoming visible. In 1826, the French inventor Nicéphore Niépce performed an experiment at his home in the village of Saint-Loup-de-Varennes where he let a surface be illuminated through his camera for eight hours. The image he produced did not disappear. And it still exists today.

Nicéphore started a collaboration with compatriot Louis Daguerre that same year, and in 1839 the public got to see their invention: the Daguerreotype. Nicéphore Niépce never got to see the finished result since he died in 1833. Daguerre, for his part, sold the idea to the French state, which allowed the Academy of Sciences to “give the invention to humanity” as a gift. Daguerre and Niépce’s family were guaranteed a lifetime pension as thanks.

The Dagerrotype quickly spread across the continent. In 1843, two daguerreotypists arrived in Stockholm. One of them, Anton Derville, became a mentor to Carl Johan Berggrén who visited Halmstad in September 1847 on his journey through Sweden. Barely eight years after the invention’s presentation, the art of photography had landed in Halland.

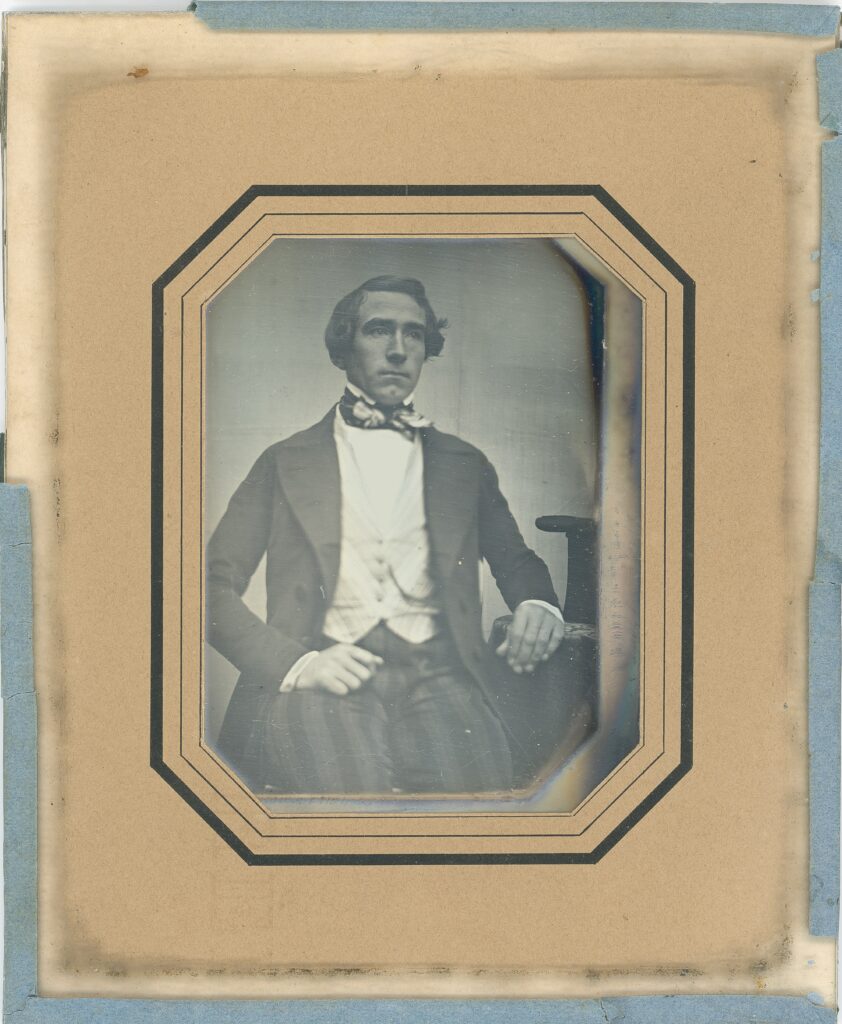

Berggrén leaves traces behind. He was visited in his temporarily set-up studio by the merchant Carl O Schéle, who was clearly curious about the talked-about novelty. About an hour later, he left the premises, with perhaps the first photograph taken in Halland. Schéle sits seemingly dreamily looking away. His clothing signals modernity and fashion sensibility: High hat, cravat and the markedly striped trousers. The watch chain is obvious, and the only thing that breaks a bit with the norm of the time is the clean-shaven chin. But perhaps he had read as it is written in a contemporary writing: “A sensible man never makes himself noticed by exaggeration in his clothing. He leaves the moustaches to the military, long hair to the farmers, big goatee to the rabble-rousers.”

The Dagerrotype became sole master of the block for quite a short time. Soon there were other techniques that were simpler, faster and cheaper. But as icebreakers and forerunners, one should not underestimate the work of Nicephorus and Louis.